‘The Duchess of Malfi’ // Arrant Knaves Theatre Company

‘The Duchess of Malfi’ was tense.

Stepping into the cavernous darkness of the Meat Market Cobblestone Pavilion at dusk is the perfect transition from mundane life to the violent, early-modern Europe portrayed in Tom Bradley’s adaptation of John Webster’s ‘The Duchess of Malfi’ (originally ‘The Tragedy of the Dutchesse of Malfy.’) Webster was a contemporary of Shakespeare, and the play, roughly based on a historic Duchess of Amalfi, is his best-known work.

Arrant Knaves specialises in bringing texts from this era to life for modern audiences, in particular the body of works now grouped together as the ‘revenge tragedies.’ Revenge tragedies are classified by their shared fixation on murder, mental illness and malcontented anti-heroes: Arrant Knaves’ last production was Macbeth, and their upcoming offerings include The Revengers Tragedy and Titus Andronicus.

Speaking with 3CR’s James McKenzie in promoting the play, Bradley, who also directs and stars, spoke about the relevance of Jacobean theatre for a modern audience. In that interview he likened the period with our own, a time of technological and social upheaval and growing disillusionment with the established social order. Bradley’s adaptation streamlines the original text for a modern audience, keeping Webster’s plot while accenting themes that resonant with 21st century theatregoers: most pertinently, men’s coercive control of women.

The performance starts with the stage dimly lit and flooded with fog. The cast files in from the wings in a funeral procession. Christina Costigan plays the good and widowed Duchess, whose evil brothers, Ferdinand and The Cardinal, implore her with every reason they have to convince her not to remarry, except for their real motivation: to retain control of her wealth, and their inheritance. The Duchess remains independently minded, though not independent. She falls in love with Antonio, her steward (a sort of mediaeval court facilities manager and accountant). They marry and have three children in secret over the six years that the course of the plot covers.

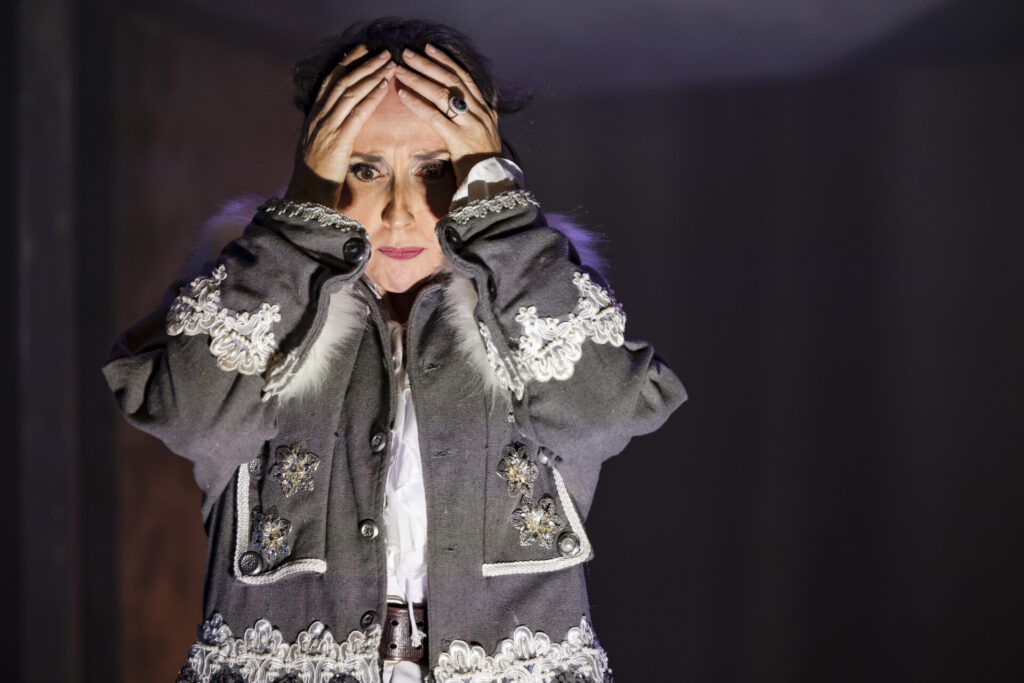

Costigan brings enough warmth and humour to the Duchess to keep her from becoming a noble, one-dimensional victim. Justin Parslow as the choleric Ferdinand and Bruce Langton as the phlegmatic Cardinal get to have more fun. Parslow brings a tremendous, almost gleeful energy to Ferdinand, whose insecure rage and incestuous jealousy require him later in the play to descend into lycanthropy (the psychological delusion that one is a wolf). The character of the Cardinal is more Tim Curry as Richelieu in ‘The Three Musketeers’ – a cold, buttoned down and kink-positive sociopath who ‘would have been Pope’ except his bribes were too large to be considered discreet. Langton’s measured portayal is chilling.

Bradley allows himself to relish the only morally ambiguous character in the play: the reluctant and cynical Daniel de Bosola, first employed by Ferdinand to spy on the Duchess. Bosola gets to deliver the self-referential asides to the audience, and the soliloquies about the corruptness of the social order and human nature. After his spying reveals the marriage, Bosola is pressed into service as the enforcer of the brothers’ violent and eventually murderous control over their sister. Too late, he changes sides, and drives the body-count up further up.

Lighting and sound are rightly kept simple, to allow the audience to focus on the complexity of the dialogue and plot. Sometimes the recorded level of effects was too loud for the actors voices to be audible, but otherwise, the direction and production was faultless. The set clusters together a number of very large frames of different heights upstage, which become hallways and hiding places as the action requires.

Costume design, like the adaptation of the script, faithfully translates the period for a modern audience. They are not strictly speaking period accurate costumes, but they are exactly what someone from our era would picture the people in that wearing, with a few effective anachronisms, like the diamond encrusted skull on the top of the Cardinal’s walking stick.

This adaptation of ‘The Duchess of Malfi’ makes the four-hundred-year-old concerns of the revenge tragedy accessible and timely, bringing to the fore some surprisingly modern and relevant themes: power, coercive control, and love, both healthy and unhealthy. It builds, tensely and slowly, to its bloody climax.

‘The Duchess of Malfi’ performs until Saturday, 24 February 2024 at Meat Market Cobblestone Pavilion. For more information visit their website.