‘Minefields and Miniskirts’ // Redcliffe Musical Theatre

‘Minefields and Miniskirts’ was evocative.

Usually the experiences of war are recounted by men, but in Redcliffe Musical Theatre’s latest verbatim-styled theatre show, the opposite rings true. Adapted for the stage by Terence O’Connell from Siobhan McHugh’s best-selling book, ‘Minefields and Miniskirts: Australian Women and the Vietnam War’ gives audiences compelling insight into the aftermath of war from the perspective of ordinary women whose lives were changed forever by their experiences.

McHugh’s interviews with 50 or so Australian women have been condensed into five main characters: Kathy the nurse, Sandy the entertainer, Ruth the journalist, Eve the volunteer aid-worker and Margaret the veteran’s wife. These five women, through monologues and songs give voice to the way women were treated during or affected by the Vietnam war, and how they dealt with post-war life.

Director, Richard Rubendra, staged this production to great effect, giving each character their own defined area, which represented their physical surroundings. Their job or role in life was similarly communicated through effectively selected props. This worked beautifully when the characters remained in their own domain, recounting their experiences as they went about their daily routine. Unfortunately, on occasions, performers moved outside their surroundings to use the full downstage area whilst telling their stories, and this disconnected the audience from the mood that had been created by the distinct staging. This directorial decision was effectively utilised when the women came together at the end to watch the veterans’ parade.

Lighting Design (by Jonathan Moss), although basic, was effective, especially during the night sky star moment, and good use was made of era appropriate songs to top and tail each act. Costumes, styled by Deborah Rubendra, were well thought out and suited each character’s personality.

The impact of this play lies in the stories and the understanding of the performers as to what these women experienced, and where each of them are placed emotionally past and present. Although there were moments when there seemed to be some lack of fear or understanding of the real horror of war, for the most part the emotional journey was strongly realised. This show was well cast and each performer was a suitable choice.

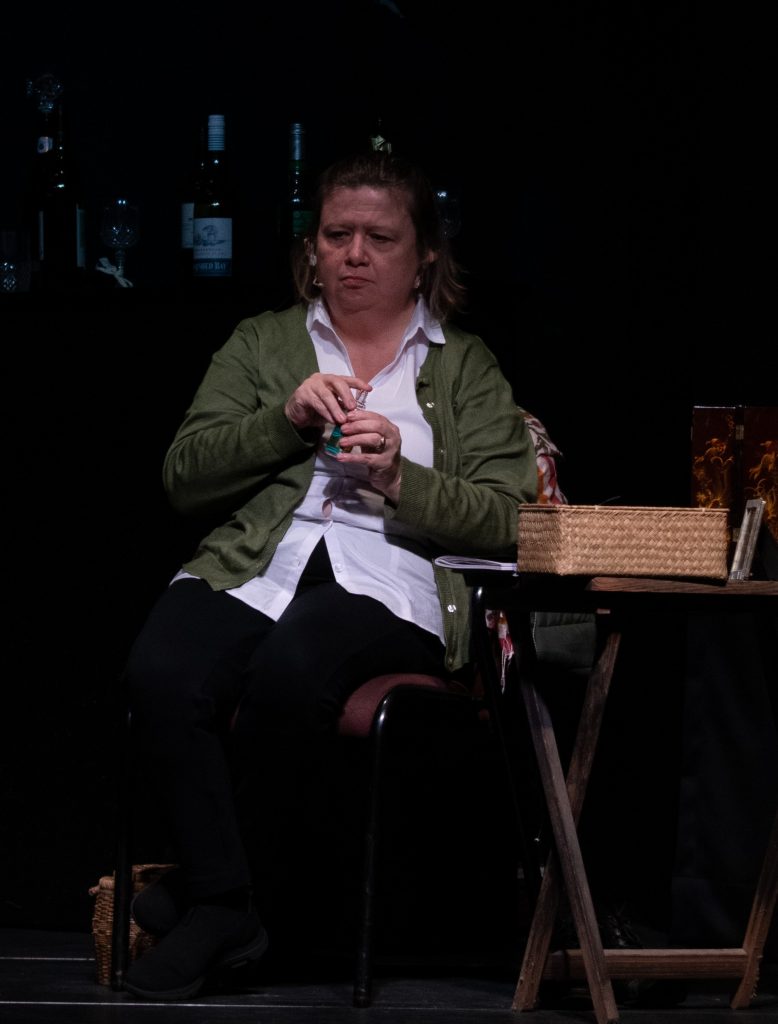

As Margaret, wife to a Vietnam vet suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Pauline Davies brought home the journey of a naïve girl who falls in love with a soldier and ends up living in fear of her husband and his condition before emerging as a warrior for the rights of veterans and their families. Her use of stillness on stage was remarkable, and her character was delivered with a strong intelligent performance.

Phillipa Bowe’s nurse, Kathy, was portrayed with passion, joy and honesty. Even though much of what she had to deal with was horrendous, her sense of humour still prevailed, as shown by her speech about the longing to taste proper food again, which enticed laughter from the audience. Bowe is also a performer who understands the power of stillness and reflection, continuing the thought process long after her monologues ended.

As the pseudo-tough journalist, Ruth, Jacqueline Kerr gave her a no nonsense approach that only thinly veils the anger and pain the character experiences during her 10 year stint on the front line. Recounting one traumatic incident involving the death of a soldier Ruth had fallen in love with, Kerr delivered a powerful emotional performance as we see the cracks begin to appear in her hardened exterior.

In the role of Eve, the volunteer aid-worker, audiences saw a caring, privileged woman who has her eyes opened to the harsh realities of war by witnessing the death and prejudice that surrounds her. Deborah Rubendra brought a nice softness to the role but due to circumstances, Rubendra’s performance was undermined by lack of projection and so a lot of her important dialogue was not clearly realised. This could have been rectified by the use of microphones on the night.

Madeleine Johns as Sandy the entertainer delivered her characters romantic tales and humorous anecdotes with gusto and a devil may care attitude to portray a starry eyed entertainer who was a little more protected from the horror side of the war. This versatility contrasted well with the other characters’ dramas. Johns is a seasoned performer but unfortunately seemed a little unsure at times, as shown by having to reference her script on stage once or twice.

With regard to the singing component of the show, all the songs in the script are wonderfully chosen to reflect the mood of the time, place and the characters. On opening night, however, although all the performers are more than capable singers, there seemed to be a slight lack of confidence in this area, so the songs didn’t quite integrate with the scenes as expected. This will likely improve in subsequent performances.

‘Minefields and Miniskirts’ is a powerful, thought-provoking piece. Thankfully, Redcliffe Musical Theatre’s production is not all heavy drama, delivering a nice amount of comedy to balance the angst. Even if you think it might not be to your taste, the play has something for everyone to appreciate.

‘Minefields and Miniskirts’ performs until Sunday, 2 August 2020, at Theatre 102 in Redcliffe. For more information and to purchase tickets, please visit Redcliffe Musical Theatre’s Website.

Photography by AKM Photography